RealClearWorld Articles

Making an Offer South Korea Can't Accept

Washington last year asked Seoul for a 50% increase in financial support to cover some of the costs of basing 28,000 U.S. troops on South Korean territory. American and Korean negotiators eventually settled on a $925 million, one-year deal that marked an 8.2% increase of South Korea’s contribution from the previous year. U.S. President Donald Trump, evidently dissatisfied, is now demanding $5 billion, a 400% increase, in the current round of cost-sharing talks.

What makes Trump’s $5 billion shakedown especially vexing is the fact that South Korea has been a very good ally when it comes to burden sharing. Trump’s insistence that U.S. allies ought to bear a greater burden for their defense, a sentiment expressed by many previous U.S. administrations, is reasonable, but some allies -- South Korea in particular -- do a good job of shouldering their fair share.

It’s unclear how Trump came up with the $5 billion figure, but this seems to be a first push at getting an ally to pay his “cost plus 50” formula -- the full cost of deployed troops plus 50 percent extra. Currently, South Korean payments go toward the salaries of their citizens employed as workers on U.S. bases and military construction expenses, though Seoul has not covered either of these two categories in full. According to the Pentagon, the $925 million Seoul paid in 2019 represents about 41% of the “day-to-day non-personnel-stationing costs” for American forces in South Korea. This percentage implies that South Korea would pay roughly $2 billion if it covered these costs in full, which comes to less than half of Trump’s demand.

South Korea is understandably flabbergasted by Trump’s $5 billion figure. Criticism in the South Korean press that U.S. troops would constitute little more than a glorified mercenary force should Seoul cave to Trump’s demand is fair, given that getting to $5 billion would probably require South Korea to pay the troops’ salaries. American negotiators walked out of initial talks, throwing doubt on hopes that the United States would eventually step back from the figure and give Seoul some breathing room. Additional reactions in South Korea have emphasized the significant erosion in trust between the allies as a result of Trump’s demand. Song Min-soon, a prominent, mainstream former diplomat, even raised the possibility of South Korea developing nuclear weapons to be less dependent on the United States.

Turkey Tests the Waters in the Eastern Mediterranean

Turkey is seeking to rewrite the rules in the Eastern Mediterranean. Last week, the Turkish government signed a maritime agreement with one of Libya’s two aspiring governments that strengthens Turkey’s position in the region. While legally ambiguous and fraught with logistical challenges, the deal represents Turkey’s latest effort to assert its dominance in the Eastern Mediterranean, to capitalize on the region’s energy resources and to restore the regional influence it lost over a century ago when the Ottoman Empire fell.

Catching Up in the Energy Race

We wrote earlier this week about how Ankara was trying to create a buffer for itself to the south, with Operation Peace Spring in northeastern Syria. Turkey’s efforts in the waters to its west have some related motivations, but they’re also about cashing in on the Eastern Mediterranean’s natural resources. For decades, Turkey has been excluded from benefiting from the oil and gas boom in the Eastern Mediterranean, which has an estimated 3.5 trillion cubic meters of natural gas and 1.7 billion barrels of crude oil. Greece, Cyprus, Egypt and Israel have been quicker and more successful than Turkey in identifying oil and gas fields along their coasts. After Israel identified two natural gas fields in 1999, for example, its government, alongside those in Greece, Cyprus and Egypt, was quick in the early 2000s to reach agreements delineating exclusive economic zones and to launch hydrocarbon exploratory patrols with multinational companies. This enables those countries not only to benefit financially from the discoveries but also to improve their energy independence.

Turkey has struggled to match its Mediterranean peers. Its seismic surveying vessels and deep-sea drills have cost Ankara over $1 billion in the past decade, and yet they have not yielded any oil or gas discoveries. Apparently devoid of such resources along its 994-mile (1,600-kilometer) Mediterranean coastline and with growing demand for and dependence on imported oil and gas, Turkey has been compelled to drill in waters that neighboring governments, namely Greece and Greek Cyprus, argue are part of their sovereign EEZs.

Confusion, Unforced Errors, and the Costs of Having No Strategy

Presidents are said to lack an effective grand strategy when they allow the ends and means of American foreign policy to drift out of balance. Walter Lippmann called it solvency: the idea that the United States must not entertain international ambitions that outstrip available resources. To pursue an insolvent strategic approach, Lippmann argued, would be to saddle the nation with an intolerable burden of risk. At some point, all overcommitments are exposed as unfulfillable promises -- jarring moments of truth that spark domestic recrimination and international instability in equal measure.

Under Trump, America’s grand strategy is more than just insolvent: it’s non-existent. Not only has the administration failed to find an alignment between ends and means -- there isn’t even agreement over what the ends and means ought to be. Does the President want to ensure U.S. primacy or shrink America’s global role? Does he believe in militarism or retrenchment? Is the United States interested in making the world economy fairer (“leveling the playing field”) or abandoning globalization altogether? The answers to these questions seem to change with alarming frequency.

Not surprisingly, Trump’s erratic approach to international affairs has made it difficult for the United States to maintain its alliances with foreign nations. From Europe to East Asia to the Middle East, several of America’s allies seem to have concluded that their long-term security interests might no longer depend upon closeness with the United States. French President Emmanuel Macron’s candid remarks that the NATO alliance has been left “braindead” by Trump are only the latest example of this growing sentiment.

How could it be otherwise? During his first year in office, Trump famously declined to endorse NATO’s mutual defense clause despite being given multiple opportunities to do so, only relenting because of sustained pressure from his exasperated team of advisers. More recently, he has ordered the withdrawal of U.S. funding for NATO’s collective budget, has called the U.S.-Japan alliance “unfair,” and has insisted that South Korea pay an exorbitant $5 billion in exchange for U.S. forces being based on the Korean Peninsula. These are pretexts, perhaps, for curtailing America’s commitments to its most important allies in Europe and the Asia-Pacific.

The problem is not that Trump is uniformly hostile to America’s strategic partners. If this were the case, foreign leaders would at least have a clear sense of U.S. foreign policy in the age of Trump. But Trump is no isolationist. He has ordered thousands more U.S. troops to bolster the defenses of nations such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Poland, and he has even suggested the conclusion of a new mutual defense treaty with Israel. These are not the actions of a President who rejects the notion of collective security altogether.

Rather, the trouble with Trump is that he has not articulated a clear and reliable vision of how U.S. alliances serve America’s self-interest. Are some alliances worth defending as ends in themselves? If so, which, and why? If not, are collective security arrangements at least an appropriate means by which the United States should pursue its core national interests? How valuable are they in comparison to unilateral applications of U.S. power? Three years after Trump scored his shock triumph in the Electoral College, no foreign leader can be sure of the answers to these questions.

The truth is that there are no general principles that guide Trump’s approach to alliances. There are some strategic partnerships that Trump views as extensions of his personal friendships with foreign leaders -- those with Israel and Saudi Arabia, for example. At other times, Trump treats allies as little more than tributaries of a U.S. Empire, as with Japan and South Korea. And then there are those allies that are having to get used to the idea that President Trump simply does not care a great deal about their security.

Trump’s failure to offer reassurance about the role of alliances in American grand strategy will severely weaken U.S. power and influence in the world for a long time to come. Even if this is not readily apparent at the moment, the problem will confront US leaders at some point. This will come about either when the United States faces an international crisis that it cannot manage alone, or when some future U.S. leader tries to implement a coherent grand strategy but finds themselves conspicuously lacking that unique power asset that every president since Harry S. Truman has deemed invaluable: an unparalleled system of formal and informal alliances to anchor and amplify U.S. power in every part of the globe.

Even those who scoff at the “liberal” international order and advocate a less activist role for the United States should be desperately unhappy with Trump’s mishandling of U.S. alliances. While realists and restrainers often balk at the steep costs that go along with sustaining the largest network of alliances the world has ever seen, their goal of reducing America’s overseas commitments will be difficult to meet unless likeminded allies can be convinced to share the burden of providing international security. In other words, alliances are still an important means at America’s disposal even if the desired end is something much less than liberal hegemony.

Trump, of course, has no long-term goal in mind when he trashes America’s alliance system. His wrecking-ball approach to U.S. alliances will do nothing to turn today’s junior partners into tomorrow’s self-sufficient pillars of global security. For all his bluster about being an expert dealmaker, the president fails to understand that foreign powers will only pursue policies that align with U.S. interests if they can be somewhat sure that their place in American grand strategy is etched in stone. By leaving America’s allies guessing about his administration’s intentions and those of his successor, Trump will leave behind an international architecture that is much less conducive to American peace, security, restraint, and retrenchment.

For more than 70 years, one of America’s unique power resources has been its global network of formal and informal alliances. No matter what “ends” they have oriented their foreign policies toward achieving, generations of U.S. leaders have recognized the advantages of maintaining stable and credible alliances. In just three years, Trump has done lasting damage to this irreplaceable source of international influence. America is much weaker as a result. It will remain so long after Trump exits the Oval Office.

With Lula Free, Is Brazil Next in Line for Protests?

Tumultuous street protests have shaken governments across Latin America, most recently in Colombia. Brazil’s leaders worry that similar protests could reach their country as well. The site of massive rallies a few years ago, so far Brazil appears immune to the violent unrest convulsing the continent. But the same kindling that took fire in Bolivia and Chile pervades their country: anger at elites, persistent inequality, weak employment prospects, and endemic corruption. While there are plenty of reasons to believe that Brazil will not follow its neighbors into violent unrest, domestic factors like the release of former president Luiz Inácio ‘Lula’ da Silva from prison could provide the necessary spark.

Just one month ago, Brazil’s government appeared ready to enter a cycle of political and economic reform. President Jair Bolsonaro finally achieved his prized legislative victory -- a critical overhaul of the nation’s pension system -- freeing up critical resources for much-needed education reform and new efforts at public security. With his government and the economy starting to deliver, Bolsonaro’s ministers are advocating tax reform as the next step to unleash the country’s considerable economic potential. According to the World Bank, Brazil spends more hours than any country on earth complying with its tax code -- 1,500 a year on average -- and more than eight times its regional peers Mexico and Argentina. Reform of such a behemoth obstacle to growth seemed like an obvious follow-on to pension reform.

However, the surprisingly destructive protests in neighboring Chile have persuaded Bolsonaro to slow the implementation of economic reforms. Brazil’s Finance Minister, Paulo Guedes, considers Chile’s economy to be an inspiration and has studied the model closely. (Like the Chilean advisors who liberalized its economy in the 1980s, Guedes also has a PhD in economics from the University of Chicago.) In light of the region’s activism, Guedes commented that he would rather not provide Brazilians with “excuses to smash things in the streets.”

Compounding these dynamics, Brazil’s Supreme Court recently intervened, forcing the release of Lula, Bolsonaro’s principal rival on the left. Lula was convicted of graft in 2017 and has served 19 months in prison, but the Court ordered him released pending the exhaustion of the appeals process.

Helping Colombia Weather a Crisis

Colombians took to the streets on Nov. 21 to protest a series of grievances. Demonstrators oppose the government’s proposed economic reforms and deplore the country’s flailing peace process. They harbor a general sense of dissatisfaction with center-right President Iván Duque. The protests reveal that Colombia is not immune to the recent wave of civil unrest that is destabilizing Latin America. Beyond the implications for the Duque administration, the growing unrest should serve as a wakeup call to the United States and the international community about the need to remedy its insufficient support for Colombia, which is dealing with the most dramatic refugee crisis in the region’s history. Failing to do so will likely lead to further polarization and instability in Colombia.

Colombia has been left to bear the brunt of the Venezuelan migration crisis, but the developing country’s humanitarian response is woefully underfunded. The international community has donated a fraction of the funding that it has disbursed to address the Syrian refugee crisis. In a plea to the world, Colombia’s foreign minister highlighted this disparity by pointing out that relief funds from the international community equated to $68 per migrant, compared to the more than $500 per migrant donated to support refugees from Syria, South Sudan, and Myanmar.

Fundraising levels for the United Nation’s Regional Response Plan have reached just half of the goal set out for 2019. A recent effort to bolster these funds, including a major international conference in Brussels this October, saw little in the way of new funding from the European Union, whose response to the Venezuelan crisis is dwarfed by its past support for similar humanitarian efforts. The Duque administration has reallocated funds from other policy priorities and shifted costs to already strained local communities and municipalities, but it needs further international support to fully address the crisis.

Colombia has absorbed more than 1.4 million Venezuelan refugees, yet there has been minimal resulting social unrest targeting Venezuelan migrants. A sense of solidarity and gratitude for Venezuela’s past openness to Colombians fleeing the country’s armed conflict has spared refugees from public frustrations. Notably, candidates in Colombia’s recent regional elections did not use the subject of Venezuelan migrants as a political cudgel, despite the clear potential for abuse. Indeed, Colombian political parties across the ideological spectrum pledged to reject xenophobia in their political campaigns.

A Failure of Leadership in the Muslim World

Bad news about China’s persecution of the Uighurs has been coming thick and fast.

In October, the Citizen Power Institute released a report on the use of forced labor. The report finds that up to 1 million imprisoned Uighurs and members of other Muslim ethnic groups have been made to work in China’s cotton value chain, which produces cotton, textiles, and apparel. In November, the New York Times released more than 400 pages of internal Chinese government documents that exposed how China organizes the mass detention of Uighurs.

On July, 22 countries issued a joint statement criticizing China for "disturbing reports of large-scale arbitrary detentions" and "widespread surveillance and restrictions" of Uighurs and other minorities in the country's Xinjiang region. The next day, 37 countries, nearly half of them Muslim-majority and none of them democracies, defended China's human rights record and dismissed the reported detention of up to 2 million Muslims.

Azeem Ibrahim of the U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute has pointed out that the acquiescence of Muslim-majority countries illustrates “’Muslim solidarity’ is a convenient and effective slogan to be thrown at domestic audiences” but, when push comes to a shove from China, you can “forget about the umma.”

China Woos the 'Trump of the Tropics'

The love affair between Jair Bolsonaro and Donald Trump was in full swing in June on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Osaka. The two presidents, who share a laundry list of commonalities including support for gun rights and hard-line immigration policies, bonded over their mutual distrust of Chinese trade policy. Changes are apparently afoot, however, after Bolsonaro -- who once accused China of trying to “buy up Brazil” -- visited with Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing earlier this month.

Brazil would like China to import more of Brazil’s value-added products and to court more Chinese investment in Brazil. One needs look no further than Foreign Minister Ernesto Araújo for a sign of how radically the Bolsonaro government’s China policy has pivoted. Araújo is a fervent admirer of Donald Trump’s and was once a staunch anti-China voice. In fiery posts on his blog, he has accused “Maoist China” of being behind a globalist plot to “rule the world”. In a remarkable contrast, Araújo recently declared that “[Chinese investment in Brazil’s infrastructure] is a useful and helpful presence for us. There are no restrictions on Chinese investment. We want more Chinese investment”.

Araújo has taken considerable pains to insist that the elevated hopes of a U.S.-China trade deal are good news for Brazil. It makes one wonder how much Brasilia fears losing the competitive advantages it has enjoyed during the trade dispute. Whatever the case, Araújo’s 180-degree turn and Bolsonaro’s trip to speak to Xi are just the latest stages of a steady rapprochement between Brazilian and Chinese officials.

Vice President Hamilton Mourão and a number of lawmakers, including Bolsonaro’s eldest son, Flavio, participated in a trip to China that was funded by the Chinese government earlier this year. Since no Brazilian taxpayer money was spent during the trip, lawmakers were able to spin it as a positive exercise in extending bilateral relations between Brasilia and Beijing -- ostensibly with no strings attached.

Iraq's Chance

While much of the West focuses itself inward, something astonishing is happening in Iraq, a country in which thousands of Western lives have been lost and the sum of Western dollars spent runs into the hundreds of billions. Iraq's future as a free and responsible nation may well depend on its outcome. The future of pluralism in Iraq’s political system may also hang in the balance, as may the long-term survivability of the country’s Christians and other minorities.

Since early October, millions of marginalized Shiites have led an unending mass protest against the entrenched corruption of the Shiite-majority government, and against the interference of its theocratic Shiite neighbor, Iran, which has spent years tightening its grip on Iraq’s internal affairs. The open opposition is unprecedented in its bravery and scope.

More than 300 people have been killed since the protests began -- most by thinly disguised Tehran-backed militias -- as Iran’s proxies struggle to stop the demonstrations. Many thousands of civilians have been seriously injured. The government has attempted to cut internet access, but pictures and video of the protests have continued to reach the outside world, sharing a story of horror and courage. Peaceful, non-violent protestors demanding a non-sectarian, secular country, with a new constitution that provides true equality for minorities and marginalized Muslims alike, are shown being gunned down by live ammunition or by the lethal use of military-grade tear-gas canisters. These weapons are fired like rockets directly into masses of unarmed people.

The demonstrations, and the violent response to them, have brought together Iraq’s majority and minority populations in a remarkable way. Christians -- including their clerical leadership -- have joined openly in supporting the protests. Signs expressing solidarity with minority communities are also widely seen, held in the hands of Muslim protesters.

America Must Try to Thaw Its Relationship With Russia

There is no denying that U.S.-Russia ties have seen better days. President Donald Trump’s attempt to improve relations between the two countries notwithstanding, Washington and Moscow view one another through a hostile lens. American diplomats are bearing much of the brunt of this shift; in the latest instance of Russian intimidation, the Kremlin arbitrarily delayed the evacuation of a sick U.S. military attaché from the Russian capital this past August.

Relations between the two nuclear superpowers can always get worse, which is precisely why Washington and Moscow should try to prevent any further deterioration. The most impactful way to inject some much-needed restraint into the relationship is by investing time and energy into new strategic stability talks while keeping peace-building agreements alive.

In the decades since the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia and the United States have built a pile of grievances. Foreign-policy leaders in Washington remain highly disturbed by what Vladimir Putin’s Russia has become: a declining power seeking to reclaim some of its former Soviet glory by sowing disinformation operations in the West and lending an economic, military, and political lifeline to kleptocratic governments from Syria to Venezuela. Meanwhile, policymakers in Moscow are angry and distrustful of U.S. intentions. They see U.S.-led regime-change campaigns in the Middle East and two decades of NATO expansion as a concerted campaign to knock Russia down and curtail its freedom of maneuver.

The situation has degenerated to such an extent that meetings at the head-of-state level, once viewed as standard practice, are now condemned as dangerous and naive. In both capitals, bilateral diplomacy has become captive to zero-sum thinking. Statecraft has been put on a short leash.

Spain’s 4-Year Search for a Government Continues

A Spanish Government Remains Elusive

Spain's Nov. 10 general election resulted in another fragmented parliament, leaving no single party able to govern alone. The Socialists won 120 of the 350 seats in the Congress of Deputies, followed by the conservative People's Party (88 seats), the far-right Vox (52 seats) and the left-wing Unidas Podemos (35 seats).

The new Spanish parliament will hold its first session on Dec. 3. After that, King Felipe IV will begin consulting with all the parties to see if a government can be formed. This process does not have a specific timetable, however, meaning it could take months. If no alliances emerge, Spain may have to hold yet another general election in early 2020. In the meantime, prolonged uncertainty about the country's political future — driven in part by the successionist push in Catalonia — risks exacerbating the country's economic slowdown.

More Coalition Talks in Tow

An alliance between center-left and left-wing parties (including the Socialists, Unidas Podemos, and Mas Pais) would control only 158 seats, well short of the 176 needed to appoint a government. Similarly, an alliance of center-right and right-wing forces (including the People's Party, Vox and Ciudadanos) would control only 150 seats, which would make it even harder for them to access power.

This means that smaller, regional parties will play a key role in the appointment of Spain's new government. Several of them, however, are pro-independence groups from Catalonia that will demand the organization of a legally binding independence referendum for the region in exchange for their support — a condition that neither the center-left nor the center-right will accept. Negotiations to form a government will thus last for weeks, if not months, meaning that Spain will continue to operate under a caretaker government with limited powers.

A Looming Economic Threat

Afghanistan's Election Should Not Prompt U.S. Withdrawal

As millions of women and girls in Afghanistan wait for the presidential election results, expected to be announced in November, they are worried. Their concern is that the country could backslide on the immense gains Afghan women have made since the fall of the Taliban. And if the United States uses a potentially chaotic election as an opportunity for a rash withdrawal, this outcome is likely.

In September, over 2 million Afghans headed to the polls, out of the 9.6 million people registered to vote. These preliminary numbers are from the Independent Election Commission, and unfortunately they show that participation among women was lower than anticipated.

Taliban violence and intimidation played a role in the low turnout. Additionally, the Commission required all voters be photographed for use with facial recognition software as an anti-fraud measure. Prior to the election, Afghan women’s-rights activists demanded this requirement be lifted as some women would be reluctant to have their photos taken, whether due to their own views or the views of a relatively conservative Afghan society.

Afghan women obtained the right to vote in 2004, and have been politically active since. However, the risk to their safety in exercising that right is disheartening. Encouragingly, despite low turnout, the Afghan people stood united in late September and had a unified message: We want peace, we want democracy, we want a bright future. The United States should stand beside the Afghan people as a partner and friend during this critical time in the country’s history.

Baghdadi's Death and the Future of ISIS

The killing of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the self-proclaimed caliph of the Islamic State, is not the end of ISIS. But what ISIS becomes now is not clear either.

Some believe that Baghdadi’s elimination is little more than a symbolic victory. Revolutionary insurgencies and terrorist organizations usually have a succession arranged in case the top leader is killed. A new ISIS leader will be named soon, and the overall danger is undiminished. ISIS will go on in various countries as a guerrilla warfighting organization and a terrorist network. It may be less centrally organized than before, but just as lethal.

The other judgment (which I share) is that killing Baghdadi is of considerable significance. Baghdadi established ISIS. He was the founding father, the heroic leader. He was the caliph of the new Islamic State created in a blitzkrieg across Syria and Iraq, just as Prophet Mohammed’s army swept out of the Arabian Peninsula in the 7th century. To his followers, Baghdadi was the personification of Islam’s long-awaited resurrection and return to dignity. Several hundred thousand local and foreign fighters traveled long distances to live in a sharia state, and they brought their families. These people pledged their lives to Baghdadi. Often the foreign fighters were the most dedicated. Only a few years after the events, it’s too easy to forget this.

The story of ISIS/Islamic State is nothing new. It’s just the most recent version of a recurring historical phenomenon. ISIS represents an ideology, an “idea.” It is a fanaticism that at its very core is totalitarian. It cannot be otherwise, because what a political movement does on the outside is a function of what it is inside itself.

America Should Embrace Restraint in Dealings With Russia

Dara Massicot of the RAND Corporation believes that the Russians will release a new military doctrine by 2020. Massicot argues that the new Russian military doctrine will contain nine fundamental changes to the previous doctrine, from 2014. Understanding these changes will be essential for any Western policymaker hoping to anticipate Russia's strategic intentions.

From the perspective of most American policymakers, the most interesting aspect of Massicot’s piece is her claim that while the new Russian doctrine will make coded barbs about Washington, Moscow will stop just shy of officially declaring the United States a military threat. This underscores the fact that, no matter what differences Moscow and Washington may have, the Russians continue to seek a diplomatic solution to tensions with the United States. However, seven other points that Massicot believes will be in the new Russian doctrine indicate that Moscow is no longer content to play by the rules of the 1990s and early 2000s, when the United States was the unipolar power.

Russia has embarked on a slow and steady revitalization of its armed forces. While the Russian Federation’s military and economic power pales in comparison to its Soviet predecessor, the changes to Russia’s military have done much to make Moscow a regional power again. In the 1990s, a succession of U.S. presidents supported expanding NATO and the European Union into regions that Moscow historically viewed as their sphere of influence. These moves aggravated Russia. As early as 1994, at a meeting of NATO’s leadership with then-Russian President Boris Yeltsin, the Russian leader cautioned his audience that they risked taking the world from the Cold War into a “cold peace.”

Welcome to the Cold Peace

The Potential War Map of Eastern Europe

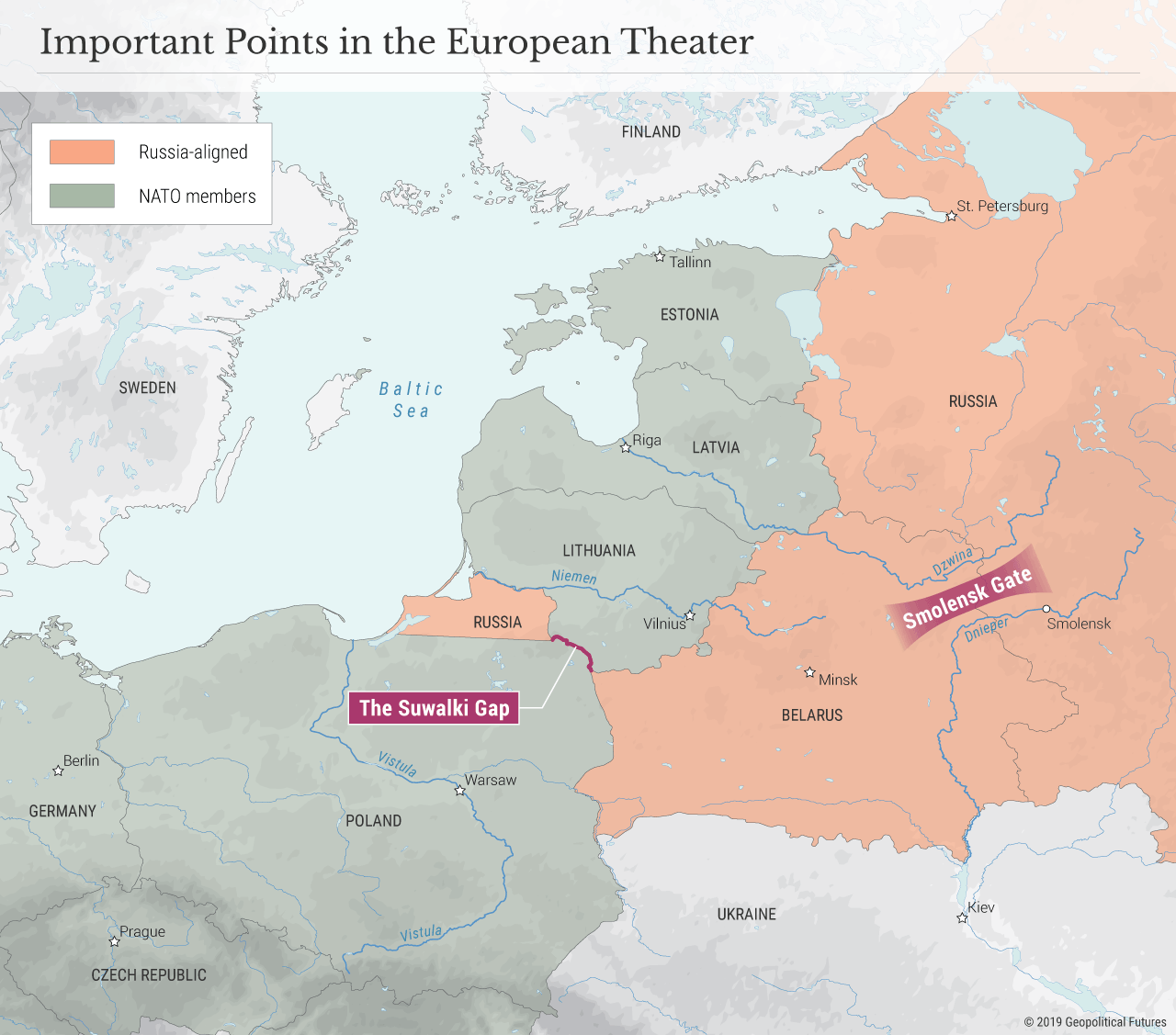

Last week, I gave a birds-eye view of how Russian military policy and NATO’s Eastern European military policy shape each other. This week, I’d like to home in on the areas in which those policies would converge, starting with the Suwalki Gap.

The Suwalki Gap

The frequently cited Suwalki Gap is the only communication route connecting Poland – the operational base of NATO and the U.S. – to the Baltic states, which abut Russia and thus are vulnerable to Moscow’s military advances. This narrow area is essential to sustaining NATO cohesion and guaranteeing the collective security afforded by NATO. In military terms, NATO’s Line of Communication, or LOC, through the gap is extremely difficult to establish and maintain; it traverses a challenging terrain over a long distance, from Warsaw to Tallinn, and since it is flanked by Belarus and Kaliningrad, it is vulnerable to Russian anti-access/area denial assets. (Indeed, the importance of Belarus and Kaliningrad cannot be overstated. They affect NATO’s general strategy, the escalation ladder, nuclear aspects, political dimension, cohesion of the alliance, and so on.)